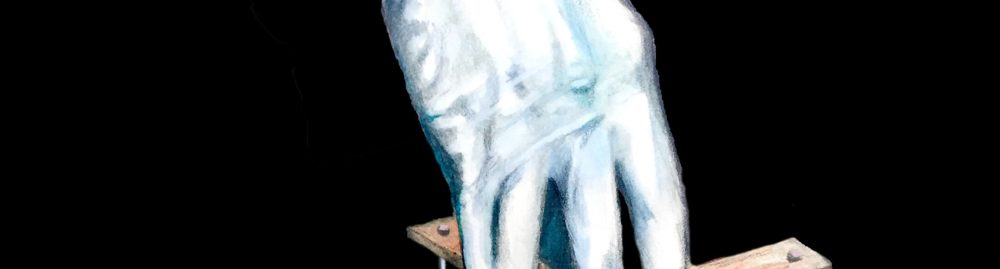

Sneak preview of new cover art by Assaf Shtilman:

Preventable Tragedies (Helen Mirkin 3)

1

Tel Aviv, 2008

The car park at Mid-City Hospital was filled to the brim and the slim young woman squeezed her way between cars, bending more than one passenger mirror in her eagerness to get to her Jeep and make a quick getaway.

Detective Inspector Helen Mirkin couldn’t stand being in a hospital environment for very long, ever since her father had been allowed to die of post-operative complications in a renowned Jerusalem hospital several years back. As with war, the patient and his or her family knew when, and sometimes why, a medical procedure was initiated, but not how it would end. Following what the heart surgeon had described as a “successful operation,” the staff had failed to maintain an acceptable standard of hygiene, thus enabling a lethal bug to flourish within the operating theatre and/or their post-operative care and silently wreak its havoc. The result: a dead father. Her father.

Now, as she weaved her way through the cars, Helen couldn’t help thinking, as she had many times before, that her father’s hospitalization had been a death warrant. All told, it had taken his doctors one month to transform a living, breathing, reasonably happy and functioning person into a defeated man, one suffering from multi-system failure. A man who no longer feared, and at certain moments may even have welcomed death with its promise of liberation from this cascade of events and spiraling torture.

Never one to trust physicians blindly as though they were the gods they craved to be, since her father’s untimely death, Helen had even less faith in hospitals and their staff and avoided them as much as possible. Her recent altercation at the Nuclear Medicine Isotope Clinic hadn’t helped restore her trust. Minutes ago she’d had a serving of radioactive cornflakes and milk at the Isotope Clinic. She had been referred there by the police medic upon admitting during the mandatory annual checkup that she was having trouble swallowing her food unless she washed it down with some water. Yet upon scheduling this upper GI test, the staff had neglected to inform her that it involved the ingestion of radioactive markers to facilitate the tracking of the semi-solids coursing down her esophagus. Having learned this to her chagrin just prior to the exam, upon inquiring about potential side-effects, Helen was concerned about exposing Sheila to her body’s radioactivity following the imaging diagnostic. Sheila hadn’t gone to school today and Helen was to be with her while her partner, Mira, was at work. Minimal dose or not, Helen needed to be sure the Tc99m marker wasn’t dangerous, for it had a half-life of at least six hours. The radiologist’s noncommittal response that she was welcome to research this online and schedule a later appointment did nothing to reassure her, on the contrary, it incensed her even further. She had needed to hear a clear communication regarding the potential hazards, and had hoped to be reassured it was okay to undergo the test.

Her mobile rang. “Mira? I’m on my way home. Should be there in twenty … don’t ask. Crazy doctor. She wanted to kick me out because I had the audacity to ask about side effects. Talk to you when I get there. Bye.”

Damn doctors. Whatever had happened to true “informed consent?” Exiting the multi-level parking structure, it occurred to her that the referring physician, the GI specialist who had seen her at the hospital’s outpatient clinic before ordering the test, might have taken the time to explain the nature of the procedure, of which most people had never heard. Knowing herself, she was sure she had asked about it. Good thing it was behind her—she should get the results in the mail in about a week.

Meanwhile she had two more tests scheduled over the next few days. None of them fun, but at least she’d know if her esophageal sphincter muscles were doing their job. She wondered if the Paula exercises she’d once learned to improve her singing voice, yet neglected of late, would kick in. They focused on the body’s sphincter muscles and trained them to act in concert, in a kinetic melody. Surely better than meds. Any meds. She promised herself that from now on, she’d devote a few minutes to training her muscles each day. If it didn’t help with her specific complaint, at least it would do no harm, and was bound to improve her vocal production, her sound. An amateur singer in a semi-professional chamber choir, her voice was important. While not in Mira’s league, for Mira was a professional singer at the Opera, she needed to be way up there, with the other sopranos.

LEAVING MID CITY, Helen made a right on Weizman Street and drove north towards Shikun Lamed, where she lived with Mira and Sheila. She’d left her former lodgings in Hadar Yosef, another suburb of Tel Aviv, and joined their small family several months ago. She had met Mira on the job, when they’d both lived in Jerusalem. At the time, Mira’s partner of many years, Dr. Danielle Hall, a clinical psychologist, had been inexplicably shot in the head in broad daylight, near the Knesset. The case had led to the discovery of a major cover-up at Jerusalem’s City Hospital, and to the subsequent arrest of several staff members, including a well-known professor who had been conducting some clandestine research. A second case involving the international Opera Music Workshop had brought them together again a couple of years later, and the rest was history. By then, Helen was living in Tel Aviv, having returned after spending a few years in the capital, to which she had been lured by love. No longer in that relationship, she had felt a pull to Tel Aviv, a less fanatic and more liberal coastal city. Eventually Mira and her daughter Sheila relocated from Jerusalem, given the budding relationship between the two women, and Mira’s work at the Opera, or Performing Arts Center as it was now called. A few of her vocal students occasionally came down to Tel Aviv for coaching lessons, and now she was more accessible to those living in the greater Tel Aviv area, and had taken on a handful of new ones. Since the opera did not pay local singers well, coaching was a good supplemental income.

Locking the Jeep with the remote, Helen climbed the few steps to the lobby and buzzed herself in. She couldn’t wait to get home.

2

The shower water was just the right temperature as Helen cleaned up, washing away the last of the hospital from her hair. What a relief to re-own her body after the check-up, which had involved being rotated for imaging purposes. The house was quiet. Mira had gone to work with her pianist—she had a rehearsal for a new opera next week, and was working around the clock to perfect her role. Opera singers did not have the luxury of having the vocal score in front of them as they performed, like Helen did, in her choir. They truly sang from the heart.

Helen was towel-drying her hair when the phone rang.

Her day off, she wasn’t expecting a work-related call. Afraid the ringing might waken Sheila, Helen hurried to pick it up. Glancing at the caller ID, she didn’t recognize the number. Probably some telemarketing nuisance. Like spam on the net, only you couldn’t block it.

“Hello?”

“May I speak to DI Mirkin?”

A hoarse voice, that of a heavy smoker. It sounded like a middle-aged male.

“This is she.”

“Forgive me for calling your residence, but you weren’t at the station, and I felt this couldn’t wait.”

“Who is this? How’d you get this number?” Unlisted, she resented this intrusion upon her private life.

“Actually, through your partner.”

“You know Mira?”

A pause. “No, but I know you’re together, and her number is listed.”

“Right,” said Helen slowly, as her mind buzzed away. “And you are …”

“My name will mean nothing to you, Boris Sencha.”

He was right about that.

“I was wondering if we could meet—I have some information you might find interesting.”

“Regarding?”

“I’d rather not get into it over the phone. Could we meet today? Just tell me when and where, and I’ll be there.”

Despite herself, Helen heard herself saying, “Aroma at the port? The Tel Aviv port. Five p.m.?” By then, Mira should be home, wanting to spend time with Sheila.

“Excellent. I’ll be reading The Economist.”

“See you then.” No reason to suspect a trap of some sort. She could have refused to meet him, but her curiosity was whetted. Not used to being sought out in such a way, she felt more like an investigative reporter than a cop. She’d take a walk along the boardwalk when they were done and watch the sun set over the sea, one of the perks of being back in Tel Aviv after years in the mountains of Jerusalem.

Helen fixed Sheila her favorite lunch in case she was hungry upon waking up, taking into account she might not have an appetite, as is often the case with sick kids. Or adults, for that matter. Although she herself had yet to be sick enough to lose her appetite. This was one of the reasons she worked out daily to keep in shape—it helped her metabolism. She alternated between going to the gym, taking brisk walks, or using the treadmill in the family den. Even though she got bored after fifteen minutes, even with the TV on to keep her company. Unless Mira was singing. Then she could walk much longer, immersing herself in the music.

3

There were still a few parking spots left in the lot nearest the northern part of the boardwalk. The beautiful wooden seafront was dotted with elegant cafes and shops, which stretched from the Reading Tower in the north, all the way to Jaffa, if you were willing to take a few detours along the way until it was completed. Unfortunately, the wooden section gave way to old pavement all too soon, some of it neglected and stinking of urine, especially in the area near Kikar Atarim and the old “Drugstore,” once a popular UN haunt for soldiers on leave. Helen wondered why they didn’t tear down the old disco and renovate the prime location to its full potential.

She pulled into an ample parking space, for which she was grateful, not wanting her Jeep to be scratched. A few years old, it continued to serve her faithfully, and she loved its emerald color. It had been a present from her father. Locking up by remote control, Helen walked briskly past Max Brenner’s chocolate emporium, which always made her think of Charlie’s Chocolate Factory, past Comme Il Faut, towards Aroma. She was curious to see what her mysterious caller had to say. It had better be good.

Scanning the various men seated at the outdoor tables, she saw no one who might fit the bill. She stood at the counter and ordered a coffee, a macchiato. When her name was called, she picked it up and sat outside.

Within minutes, a man holding an unfolded copy of The Economist approached her. He had silver hair slick with brilliantine and thick glasses, through which shrewd eyes appraised her. “DI Helen Mirkin?”

She nodded.

He put down his periodical and said he’d order a coffee and then join her.

Soon back, he introduced himself properly. “Thanks for seeing me at such short notice. My name’s Boris, Boris Sencha. I’m a senior executive, the CEO actually, at Affordable Alternatives or as we say, AA, for short. We are a subsidiary of Bandela Industries. You’ve probably not heard of us—we’re based in Milan, have offices in various cities, including here in Tel Aviv, where I work. Among other products, we produce food additives, such as MSG, natural flavorings and partially hydrolyzed proteins—pseudonyms used to conceal MSG. Labeling is required only when MSG is added as a direct ingredient.”

Helen nodded, thinking the legislation should be changed, but also wondering why he was telling her this and what else his company might be concealing. She’d heard of these reprehensible practices, and generally avoided consuming processed foods and ‘natural flavors,’ a misnomer if there ever was one. No soup powders and flavored rice for her, thank-you very much. At home, she and Mira bought organic chicken and eggs and as many organic vegetables as they could afford, although neither were confident they were truly organic, ever since a well-publicized scandal in the past, when EU inspectors unveiled false claims made by local farmers regarding the fruits and vegetables they exported. Apparently the earth itself was contaminated. But having no viable option other than growing produce themselves, which was difficult to do in the middle of a bustling city, they bought ‘organic’ foods, especially for Sheila. Nine years old, she still had a lot of growing up to do.

She studied him as she took a sip of her coffee, by now lukewarm. Damn. She couldn’t be bothered to have it heated in the microwave, which made it bitter.

“A few years ago,” Boris was saying in a conversational voice, “the founder and primary shareholder of Bandela Industries passed away. His daughter and sole heiress, Ms. Martha Spotnik, decided to jump-start a new company, Affordable Alternatives, of which, as I mentioned, I am CEO.” Big smile. He appeared proud of himself.

“In addition to producing the food additives I mentioned—our staple food—,” he seemed oblivious to the irony of what he had just said, “AA researches and markets super foods, foods which are universally beneficial and may even obviate the need for certain medications. Sounds good, right?” He looked at Helen, who nodded slightly in response.

“Except this is only the beginning of the story—”

“I’m all ears,” said Helen, her appetite whetted, wondering what was coming. “But I must warn you, this is my day off, so it had better be good.”

He shrugged noncommittally. “Two years ago we supplied health food stores with Goji Berries grown in Asia. They are renowned especially for their anti-oxidant properties. Used in conjunction with certain other natural foods they help dissolve the extra fat in persons with Fatty Liver, or FL, as we refer to it.”

He looked at her briefly and then continued, “While the prevalence of FL is unknown, since most people don’t undergo an ultrasonic test of their inner organs, there are estimates that a considerable percentage of the population suffers from it—often unawares, as there are no visible symptoms. This is so particularly among the overweight or obese.” He paused for effect. “The good news is that FL is reversible and can be controlled.”

“Good,” said Helen, wondering where he was leading, and how all of this concerned the police department. Always on the go, she didn’t stop long enough to accumulate fat. Although not a health freak by any means, there were periods when she remembered to feed her brain omega-3 and buffered vitamin C on a daily basis. She often began her mornings with a freshly squeezed vegetable juice cocktail, sometimes getting ideas from “The Juicing Bible.” Mira had started drinking them too, and Sheila like freshly squeezed apple juice. Her thoughts moved to her family, with whom she wanted to spend time, and she felt her patience wearing thin.

Her companion sipped some water. Clearing his throat, he took a big breath before continuing.

“Although there is currently no specific medical treatment for FL, various experimental drugs or treatments are being considered—including a drug we ourselves have developed—Xinfon. We’re testing its efficacy vs. natural Goji Berries and placebo via what is referred to as a ‘randomized double-blind study.’ Ideally, the research team should also test it against diet and exercise regimes—perhaps they’re afraid of the results.”

He paused to wipe his brow using a clean white handkerchief that he took from his vest pocket, cleared his throat again and continued, “To be honest, widespread public knowledge about FL being reversible through diet and exercise, especially if caught on time would most likely obviate the need for this new drug.”

By now, Helen had had enough. “So why not make an honest living selling drugs the consumer really needs? Why create an artificial need the public can do without? In any case, I fail to see what this has to do with me, with the police department.”

He took her rhetorical questions seriously. “An idealist, are you? But naïve, if I may say so.” He smiled at her. “Wouldn’t you agree that most of what our society consumes are things it can do without? That we’re brainwashed by advertising—an industry that banks on and cultivates the herd mentality of ‘keeping up with the Joneses?’ Why, I’ll take it a step further—governments in so-called democracies, while seemingly engaged in upholding democratic principles, are often in collusion with numerous multi-national corporations—be it pharmaceutical companies, small arms manufacturers, the tobacco industry. Although politicians are quick to deny it, politics and money have always gone hand-in-hand. These multinational corporations can afford strong lobbyists, and they fork out generous donations to promote their case. Amazing what a handshake coupled with someone looking the other way can do, what with everyone getting to line their pockets. The governments have their pet nationals landing fat contracts, and the national revenue increases when they pay the minimum corporate taxes incurred, taxes that they are unable to evade …”

A nice breeze from the sea ruffled the wooden patio umbrella sun shade, which swayed slightly, and he moved his chair.

Warming up to his subject, he went on another tangent—assuming he’d wanted to talk about Xinfon. “Did you know that the Ministry of Health regulation of adding fluoride to our drinking water and toothpaste puts us all at risk—because fluoride is actually a neurotoxin?” Sencha now asked her in a conversational tone. “As its name implies, it kills neurons. And it accumulates in the brain … are you aware that despite what people think, there is no real proof that fluoride makes for less cavities?” He laughed.

Helen was feeling increasingly antsy. Surely this had nothing to do with his reason for contacting her. Against her better judgment, she decided to give him another minute to get to the point. Perhaps he needed to build a rapport with her, to feel safe, before confiding in her.

“Why, Detective—the pharmaceutical and medical industries work hard to create at least half, if not more, of the conditions they purport to cure. It’s a business. They must ensure a steady supply of customers …”

Okay. It was time to put a stop to his diatribe. While what Boris Sencha had to say had a certain appeal, raising the question of medical ethics and corporate misbehavior, Helen failed to see where all of this was leading, and especially, why she should be pulled away from her precious family time to listen to this. Weary of his digressions, she said, “I must get going. What is it you wanted to tell me, Mr. Sencha? Can you please cut to the chase?”

He gazed at her through his thick lenses, his beady eyes small but focused. “Detective, I’ve followed your career since the so-called “Rosebush Murders” in Jerusalem—the scandal with City Hospital and that devilish Professor—what was her name …?”

“Rediabolle,” said Helen, slightly mollified, her curiosity piqued.

“Right. I know you’ve seen with your own eyes what our esteemed medical profession can do in the name of science—or is it self-aggrandizement? She was after the Nobel Prize, was she not?”

Helen nodded.

“Well, like you, I’m damn tired of wasting resources, rather than investing them where they’re truly needed …” He looked at her as though debating how to proceed.

“You see—I suffer from a serious ocular problem for which there is no cure. Surgery is out of the question. Since my condition is relatively rare, the drug companies have no interest in sponsoring clinical trials for innovative medications capable of treating it. Not much money to be made …” He laughed ruefully. “Not even the company I work for will lift a finger …” His voice faltered. “Although, in my estimation, they have the resources to reverse, or at least check my condition, delay the progression of disease for a while. But they turned down my proposal, my request. I feel as though they’ve dealt me a death sentence, for soon I will be as blind as a bat.”

He lowered his gaze, then stared off into the ocean.

“I’m sorry to hear that,” Helen said out of politeness, feeling she couldn’t not say anything, wondering why he was telling her this.

Pausing momentarily, Sencha found renewed strength

He took a deep breath and met her gaze.

“What they’re doing is against my principles, and I will not protect them. They’ve been using ‘extended access’ patients as if they met the inclusion criteria and were suitable for the research protocol. They’re not. Frankly, to me, this suggests that they’ve probably adopted other lax methods as well. They must be cutting corners in other places. Clearly this will skew the results. Why even bother doing the research? Where do they get off—those greedy bastards? If you ask me, they only care about securing the FDA’s approval, and ultimately, lining their own pockets. Believe me, I’ve seen a thing or two, in my time. I’ve blocked it out, for the most part, but I have no illusions about business and business people. But now they’ve left me out to dry, this is personal.”

By now his face was flushed a deep pink.

So that’s what he’d wanted to tell her. What a long preamble. And what a waste of her precious time.

“Unless you have evidence of further irregularities, on the face of it, this does not seem to be a matter for the police. Why not involve the Ministry of Health? Surely they’ll have something to say?” asked Helen more calmly than she felt. “If they deem it necessary, they’ll involve us.” She looked at him expectantly.

“I considered that. But you see … Professor Nimrodi, the Head of R&D at Affordable Alternatives, is well-connected. Which means that someone at the Ministry of Health could bury this before you can say Jack Robinson. You see, his ex-wife works there. I happen to know that they’ve remained good friends and have joint custody of their four children. She runs the Human Resources Department. Consequently, she’s on intimate terms with all the professors—whom I’m sure would be happy to score points with her. Everything is based on interests. That’s why I decided to come to you first.”

“Right. Look, I must get going, this has taken much longer than I’d anticipated. I understand you’re making serious allegations about the ethics involved in the methodology of this research project—or should I say lack thereof? We can’t qualify as the Quality Assurance Committee, but I’ll run it by my colleagues. In any case, you’ll need evidence of wrong-doing, if you can get it. You understand?” She looked him in the eye.

“Got you,” he said, but his black eyes revealed nothing about his feelings on the matter. It was as though he’d just erected a wall between them. She assumed he was disappointed by her reaction. So be it.

4

Lahav 433: National Serious and International Crimes Unit (NSIC) Headquarters, Lod.

“So we have a disgruntled CEO with a belly full of recriminations, claiming the methodology of an ongoing research protocol for a new drug for Fatty Liver is suspect: that the actual subjects are not limited to those specified in advance and this should invalidate any claims regarding the validity and generalizability of the study—in other words, the efficacy of the experimental drug is questionable. Moreover, he feels that this is just the tip of the iceberg, that there must be other serious shortcomings, but so far has not substantiated his claims. Well, surely this is a matter for an Ethics Committee, not the Department,” said Chief Melamed, the head of the greater Tel Aviv area’s NSIC Unit, to which Helen belonged. A few years away from his pension, he was still a handsome man, tanned from bike riding every Saturday morning with a group of like-minded cronies from the force.

“In principle you’re right, Chief, although it could be argued that the violation of the research protocol in a project partially funded by the World Health Organization, represents a case of ‘receiving something with intent to deceive,’ ” countered Helen. “Moreover, the invalid results may adversely affect the target population, which is thus at risk. This leads me to believe that a case can be made for criminal negligence, or at least for the ‘total disregard for the safety and well-being of human subjects.’ How about we ask the Public Prosecutor what his position is?”

“Why don’t you?” said the Chief, who respected his top investigator’s reasoning powers. “Although I strongly suspect he’ll say it’s MOH’s judgment call whether or not to involve us. And I’ll bet they’ll want to keep a low profile, try to avoid this making headlines, stick to disciplinary action. But by all means, keep me appraised, I’m curious. And perhaps Mr. Sencha will be in a position to substantiate his claims, as requested. Meanwhile, to business. I’ve got to clear my desk, the Minister of Public Security is always on my case about something.” He sighed. “This what they pay me for.”

“HEY PARTNER, CAN you meet me at the Forensics Lab?” asked Detective Sergeant (DS) Amnon Tsaddok.

“Sure thing. See you soon,” said Helen, who had just gotten off the phone with the Public Prosecutor’s office.

The internationally renown Division of Identification and Forensic Science based at National HQ in Jerusalem, had recently opened an additional new facility, a state-of-the-art Forensic Lab. It was located next to Interpol’s Israeli National Central Bureau (NCB) in Airport City, the real-estate dream propelled into being by the opening of Terminal 3 at Ben Gurion International Airport in 2004.

At this hour there was little traffic, and Helen, who had been in the city, made it there in no time. She met Amnon on the first floor. Although her junior on the force, Amnon had several years of experience under his belt, and could work independently when necessary.

He wasted no time in bringing her up-to-date on an ongoing attempted rape case. A neurosurgeon had been attacked on her way to her car in the middle of the night. She had just finished a long surgery, having been summoned to deal with the aftermath of rocket attacks from Gaza, launched against the inhabitants of Sderot.

She’d put up a fight, but the perp had escaped. “Regarding the transfer DNA—thanks to CODIS we have a match—a fishmonger working at the Ramleh-Lod souk, Ismail Hussein. He’s from a village in the West Bank. He was visiting a co-worker, a fellow who almost got his finger chopped off at the fish market. Unclear why Hussein was still at the medical center in the middle of the night. Maybe he couldn’t get home to the Territories on time, given the erratic check-post hours, and figured it would be easier to get to work the next morning directly from Tel Hashomer.”

“So this was an opportunistic crime?”

“Looks like it. Let’s see if he has any priors,” said Amnon, tapping busily on his iPad.

“Right … hmm. Petty stuff … some problem with a neighbor, ending in a brawl. He was also arrested last fall at a joint protest of Palestinians and activists from ‘Peace Now,’ a demonstration against the existence of the West Bank Wall near Bil’in. The folks at the Ministry of Defense have been dragging their feet, and even though they screwed up, it hasn’t been rerouted yet. This is his first sex crime.”

“Gotta start somewhere.” They laughed briefly although neither was particularly amused with the gallows humor; they were all too familiar with the realities of sex crime victims, often injured for life. There were altogether too many post-traumatic stress disorder cases as it was, what with the plethora of wars, suicide bombers, and missile attacks on civilian targets in both southern and northern cities. Not to mention domestic violence in its various shapes and forms.

“Good,” said Helen. “Let me know when you have the perp in custody. The uniforms can handle it. Meanwhile, I need to take care of some stuff—and see if we have a new Pharma case.”

“Oh?” His curiosity was whetted.

“The MOH thing.”

“Ah. Your whistleblower case.” This wasn’t what he’d been expecting. “Let me know if you need me on it. I very much doubt we’ll be involved. Unless there’s more to it than meets the eye.”

“That’s the one I’m checking out with Legal. I agree, I don’t think it’s up our alley. They’ll let me know if they recommend we take action, but without hard evidence of some actual crime being committed, it’s very unlikely.”

She waved her goodbye to the good-looking detective dressed in black Levis and a forest green polo shirt that set off his tanned face and arms. She liked the way he looked, and she liked him, appreciated his youthful energy.

She ignored the elevator and took the stairs.

Murder in the Choir (Helen Mirkin 2)

MURDER IN THE CHOIR (Hoopoe Publishing, 2016)

In this second Helen Mirkin novel, upon her return to Tel Aviv, Detective Inspector Helen Mirkin is tasked with finding opera singer Araceli Pena, who uncharacteristically has missed two Wozzeck rehearsals before opening night. When she is found dead in bed, the circumstances of her death are far from clear.

The investigation takes DI Mirkin behind the scenes, to the mercurial world of the annual Opera Music Workshop, rife with competition and backstabbing among the singer’s colleagues, many of whom dream of being awarded the Seagram Grant to study under the best coaches New York can offer.

When the meteoric composer Israel Berger is shot dead shortly thereafter, the stakes are even higher for DI Mirkin, as the music world she cherishes seems to be under attack. Are the two deaths related? Can the Opera Music Workshop survive? Can DI Mirkin open a new chapter in her life and find happiness and love?

MURDER IN THE CHOIR (excerpt)

1

Bat Yam, July 2011

Araceli Pena stops singing in the middle of a high note, unable to continue with the attacca. Her heart is beating faster than usual, her face hot and flushed. Far from menopausal, it none-the-less occurs to her she must be experiencing hot flashes, and she wonders what is wrong with her.

At twenty-nine, she is at the peak of her career as a dramatic soprano. When the summer workshop ends, she will return to Madrid, so she can be with Conchita and decide what to do with the rest of her life.

In the fall, she is to start a much-coveted fellowship at the Music Hall and Opera House of New York, where, for the duration of a season, she has a chance to sing under the very best. She has worked very hard for it, her efforts recognized by Carole Zinelli and Alberto Coccio, and the others at the Opera Music Workshop. Held every summer near Tel Aviv, it attracts young singers from all over the world, and is often a jumpstart for many of their careers. This is her second year.

While her home base is Barcelona and its famous opera house where she has sung some minor roles, she has some occasional engagements in other cities, spending as much time as she possibly can in Madrid, to be with Conchita. She wishes Conchita were here with her now.

Conchita provides her with an oasis, a welcome and much-needed respite from the competitive environment she inhabits, with its constant tensions, both visible and subterranean, but palpable none-the-less, and the need to constantly prove yourself again and again, giving it your utmost. While she loves what she does, Araceli doesn’t have the luxury of a writer or painter, who, working alone in their studio, can revise and polish the work until it positively gleams. An opera singer is particularly vulnerable to the constant ebb and flow of the life stream, with its sudden gushes and swirls that threaten to invade one’s singing unannounced in real time, that is, on stage. It is necessary to be super concentrated and deliver one’s lines in the appropriate intonation at precisely the right nanosecond, always conscious of the progress of the music, with its changing key, harmony and dynamics, as well as variations in both the conductor’s and other singers’ interpretations. Although rehearsals, technique and experience can help deal with the unexpected, in the form of unbidden raw emotions, colds and breathing difficulties, the more you shine in the limelight, the more you have to lose. It is not easy to recuperate from a bad review or a raised eyebrow of someone whose opinion matters.

The frazzled soprano shakes away these thoughts, opens her eyes and looks around slowly. Despite her preparation, the air has fizzled out in the middle of the phrase, and her throat is as dry as the Sahara. Is she having a panic attack or simply dehydrated?

Alberto Coccio stops the rehearsal with his baton and an involuntary scowl. What is going on with his Marie?

“Araceli?” He peers at the olive-skinned young woman through the thick lenses of his spare glasses, unable to find the regular pair this morning. He has a pleasant baritone.

“I’m sorry, Maestro. I don’t know what’s the matter with me—I need some air. I find it very hot in here.”

He strides over to the window and opens it, the air conditioning obviously not enough. Addressing the small group of singers on stage, he says: “OK, guys. We’ll take a fifteen minute break. If any of you leave, please return on time, as we’re behind schedule as it is.”

But no one shows any desire to leave. On the contrary, they come up to Araceli to see how she’s doing. As Marie, she has one of the leading roles in the opera they’re rehearsing this morning, and since this has never happened before, they’re concerned. They like Araceli, who is always so well prepared, even though German is not her native tongue, take pleasure in her impressive range, with its magnificent highs and generous lows.

“You okay?” asks Alex, the handsome baritone who sings the central role, Wozzeck. He places the fingertips of his left hand on her forehead.

“My, you’re hot,” he says. “Let me get you some water.” He straightens up and brings her a fresh bottle of mineral water from a pack someone left in the corner.

Araceli drinks thirstily, draining the bottle in one go. “God, I was parched. Thanks, Alex.”

He smiles, his demeanor softening; lately he’s been preoccupied, and he hasn’t hidden it very well, being less open to the usual banter and camaraderie with the other singers than he might otherwise have been, probably coming across as overly serious and task-oriented. Like Araceli, he wants his girlfriend by his side, but that’s not going to happen. At least not this year, judging by Zinelli’s reaction when they last spoke.

Another singer, the Drum Major, a baritone (considered by some a heroic tenor or ‘heldentenor’) blessed with a rich dramatic voice, joins them, patting Marie gently on the shoulder. “I’m glad you seem to be feeling better. I was getting worried,” he says. They have a role to play, and feeling a tad unprepared and distracted by some family matters, he knows he needs as much rehearsal as he can get.

“I’m much better, thanks. No need to preoccupy yourself.”

But her own mind keeps spinning. She and Conchita have been together for almost two years, and the frequent separations, while something they have learned to live with, are increasingly difficult, especially if long, like this one, and more so for Araceli, although she doesn’t like to talk about it. She cannot imagine what it will be like to spend nine months in New York without her Conchita. And it’s not as if either can afford to travel back and forth. Conchita makes fine jewelry, and like Araceli, is a salaried worker. And given Spain’s fiscal challenges, not to say serious debt, her pay, while decent, is hard to live on. Bottom line, there is no way she can jeopardize her career, which is just taking off, after a long wait on the runway. On the other hand, she wants Conchita by her side, is weary of living between suitcases, constantly on the road, apart from her lover. The two essential needs for love and work don’t appear to be reconcilable, and she will have to choose between her career and her beloved—at least for the foreseeable future.

She can’t bear to think of it right now, forces herself to look at the conductor.

Coccio is relieved Araceli isn’t coming down with something—she’s seemed a bit run-down this past week. He can’t afford to lose his key singer, of whom he’s proud, like a father. She’s come a long way in just one year. The fruits of their work together last summer are clearly present in her delivery of her lines, her intonation, and she has mastered her passion, learnt how to channel it into her singing. Carole also worked hard with her, recognizing the talent that needed to be nudged in the right direction, cultivated. They had both recommended her for the fellowship, excited to be a part of her burgeoning career. She would go far, this one. They’d agreed that when they were back in the city and she too was in New York, they’d keep an eye on her, making sure Araceli maximized her considerable strengths and steered clear of the predictable pitfalls for someone of her considerable talents and temperament. There were certain personae at the opera house that simply could not be crossed—at least not without dire consequences. Forewarned was forearmed.

“I’m so glad you’re feeling better,” he tells Araceli. “Let me know when you feel up to it, so we can resume where we left off.”

“I’m fine—I don’t know what happened to me. I imagine I was dehydrated,” the black-haired singer tells him. She pushes back an unruly forelock. Her green eyes have recovered their usual sparkle. “I’m ready when you are,” she says gracefully. Her English has a gentle Spanish lilt, which he finds soothing.

“Okay then. Let’s start at bar …” says the conductor. “The entrance to Marie’s aria.”

The pianist nods, and plays the overture.

2

On the thirteenth floor of the conveniently located Tel Aviv Hilton, there are few people at the executive business lounge at this hour, and mostly pretzels and nuts, and a few basic appetizers for the eternally hungry are available to complement the complimentary drinks.

The view however, knows no bounds, as Carole Zinelli, a recurring guest from New York, who spends her summers in Tel Aviv directing the prestigious Opera Music Workshop, gazes out to sea—past the sail-decked marina, its manmade surf breakers and the old-new beach promenade from Jaffa in the south, past the hotel area and the old port of Tel Aviv, now a popular hotspot, to the gaudily decorated Reading Power Station located on the northern bank of the Yarkon River’s estuary into the sea. A solitary gasoline tanker is visible just north of Reading; when empty, it will return to the mother port of Ashdod for refueling.

Today Zinelli left work early to tie up a few loose ends before the evening concert and to meet an old friend. Having immersed herself in its calming waters, by now Zinelli’s had her fill of the sparkling blue unruffled Mediterranean, and focuses on getting something to drink. As she waits for the espresso machine to finish dripping steaming Italian coffee into a thick porcelain cup, her distinguished colleague, Jacques Elkayiff joins her, beige summer cap in hand, revealing a polished copper-colored crown amidst a silvery frame of surprisingly thick hair, testifying to early mornings at the beach, before the weather became impossibly hot and humid. Having come in from the overpowering sauna outdoors, he’s grateful for the hotel’s rejuvenating air conditioning.

“Ma chérie,” he says amicably, kissing Zinelli’s proffered hand the old-fashioned way. In his mid-seventies, he still fancies himself quite the ladies’ man. “It was not necessary to page you. One of the waiters was leaving and kindly let me in as soon as I mentioned your name.”

“Maestro,” she murmurs. “Just on time. Café crème?”

“Café crème. Café crime, arrosé sang ! … ” he responds merrily, quoting Prévert.

“No, no, no, no sardines,” he says, still referring to the poem, his eyes taking in the modest spread. He rubs his hands in anticipation. His generous stomach bulges slightly as he takes a handkerchief from his right pocket, his pants held by burgundy-colored suspenders.

Zinelli, familiar with the poem and appreciative of her companion’s wry sense of humor and eccentric habit of interspersing poetry in his conversation, nods, but having other things on her mind, doesn’t give much thought to what he is saying, even though it remains somewhat ambiguous.

“Do they have a decent Armagnac?” he inquires, helping himself to a handful of cashew and pistachio nuts.

“Hmm, how about this?” asks Zinelli, giving the liquor bottles on the top shelf a quick look-over and selecting one. “Actually, it’s either this or a cognac—not a very good one, I’m afraid. Jerez.”

Drinks in hand and a plate of mouth-sized quiches and tiny egg salad and eggplant sandwiches between them, they settle down comfortably in two perpendicular leather armchairs facing an LCD screen, which thankfully, is turned off. Neither is in the mood for a global news update, having local business to attend to.

3

A couple of days later

I’ve never heard you sing like that!” exclaims Hannah, my voice coach. “You’ve progressed to a whole new level of emotional expression!” She gets up from the piano and reaches out to hug me. I am taller than she, but she manages just fine. “I have goose-bumps,” she announces as she flashes me a big smile. “That was totally linear.”

I smile back, proud and embarrassed, take a deep breath. It’s true. I’d felt the Berg songs pour out of me like a good brandy coating a wide stem glass. “Must be your not giving up on me,” I tell her, for lately I’ve come in for voice lessons without having practiced in the interim, and the thought of taking a break has crossed my mind more than once. Somehow, the days never seem long enough, especially since I’ve relocated to Tel Aviv after having spent a few years in the capital. And I could sure use the extra dough, as I have been overreaching my already meager budget. I am not getting any younger, and need to plan ahead, especially if I want a family, which I do (most of the time.)

“No,—it’s your doing,” she says firmly. “The musical lines moved forward all the time, and I could feel the expression of feeling—each singer has feelings but the trick is to be able to deliver them to the audience. Which reminds me—tell me, are you coming to Carole Zinelli’s Master Class tonight? One of my pupils will be singing, and I promised I’d be there.”

“Wouldn’t miss it for the world,” I inform her. “I love her classes. And if I’m not mistaken, it’s the last one open to the public this year, as they’ve just started the nightly concerts. Unless of course, something comes up at work—you know how it is.”

“Well, let’s hope the crime rate in Israel will actually decrease during the Opera Music Workshop,” she says with a smile. “Because you can definitely learn a lot from her, and Alberto Coccio. It will come in handy when you have a recital.”

“Hope to see you tonight,” I tell her, as I disconnect my minidisc from the electrical outlet, making sure to turn off the mike so the battery doesn’t run out. I put away my scores, scattered liberally on her armchair. “Gotta run—thanks for a marvelous lesson.” I mean it—I’d come in on my lunch break, somewhat tired and frustrated by my lack of preparation, but am now feeling energized and optimistic about my singing, the recital, and life in general, as the adrenalin pumps through my body, and the endorphins hum.

I walk to my car, an unmarked sedan and whistling, get in and fly off to the Major Crimes Division, Yarkon Station, relieved I didn’t incur a parking ticket, since the municipality officials in this area are legendary.

Yarkon serves a large catchment area and normally the Tel Aviv precinct is a zoo. Like shrinks, cops have free theatre every working day. However this afternoon it is relatively quiet when I get there, a lull before the next storm, and I make myself an extra strong espresso rather than the customary office “Turkish mud.” Two of my former Jerusalem colleagues won the lottery last year, and in a generous mood, had sprung for an espresso machine. Truth be told, they no longer have to work for a living but they have been partners for years, and love their job. Like me, they felt a need for a change of scenery, the reason they transferred here.

As I flip through my messages, one of them catches my eye: “Contact Carole Zinelli at … ” I punch her number, and wait expectantly for her to pick up, curious as to why The Woman herself would call me. What timing. We know each other by sight but have never actually exchanged words before.

4

Traffic is slow approaching Jerusalem Boulevard, one of Jaffa’s main arteries.

I continue towards Bat Yam and the venue where the opera music workshop is held, its best asset being an easy access parking lot. I rush inside to Zinelli’s office.

“Detective Inspector Helen Mirkin, Major Crimes Division, Merhav Yarkon,” I inform the spiky gel-haired woman who nods in acknowledgement. She checks her watch, 3:30 pm on the dot.

“Carole’s been expecting you—you can walk right in.”

I do.

Zinelli is on the phone but makes eye contact as I walk in, continuing speaking, “I don’t care what time it is there. This is important. I’m counting on you. Gotta go.” She returns the phone to its cradle, and says, “You must be DI Helen Mirkin—You look familiar—As I mentioned on the phone, Mira Morenica suggested I call you—says she knows you from Jerusalem.”

I nod. I’d met Mira two years ago, when still stationed at Zion Precinct. I’d been called in when her partner, Dr. Danielle Morenica-Hall was shot dead at the Wohl Rose Park, an investigation that had been widely publicized.

“One of our singers, Araceli Pena, hasn’t been attending rehearsal—she’s missed two already: last night and this morning. She’s singing Marie in Wozzeck at our final concert, and I’m concerned something’s happened to her—she hasn’t phoned in or anything, which is unlike her. She’s staying in Tel Aviv at the Rosenfeld residence during the workshop, house-sitting while they’re abroad. The phone there doesn’t seem to be working—we haven’t been able to get through, and believe me, we’ve tried.” She rolls her eyes to make her point. “I even went there myself when she didn’t come in this morning, but there was no response. That’s when I decided to involve you.

“I’d like you to pick the lock or force your way in, or do whatever it is that you people do and see what’s with her—maybe she’s running a high fever or something, and can’t get to the phone—I don’t know what to think! And there’s no personal cell phone we can call.” The pitch of her voice rises as she says this, and it‘s obvious she’s extremely upset.

Araceli Pena has everything going for her—I’ve heard her sing in one of Alberto Coccio’s master classes; she is a wonderful dramatic soprano whose music flows right through you, awakening dormant feelings and making you feel vibrantly alive. Professional to the hilt, she’s hardly going to blow it with opening night so close.

“What’s the address?”

Carole squints at her cell phone and says: “Tina and Moises Rosenfeld, 13 Galgal HaMazalot Street, Neveh Tsedek. Near the Suzanne Dellal Center.”

I nod. “Phone number?”

“She hates cell phones, doesn’t have one, at least not when she’s here. The landline number there is … ” she rattles off by heart. “But as I said, I’ve called numerous times and there’s no answer.”

“If I don’t find her there, I’ll check with the phone company, see if there have been any incoming or outgoing calls. Either way, I’ll be in touch,” I tell Zinelli.

She nods wearily, “Please.”

On the phone again, she is probably dealing with another emergency.

***

Continue reading:

Available in print (POD), Kindle or e-Pub formats.

IF YOU LIKED “MURDER IN THE CHOIR”

- Be sure to submit a short review, to help other readers decide whether they want to read it. Thanks for taking a moment to do so!

- Like my Author Facebook Page.

- Sign up for new releases.

The Rosebush Murders (Helen Mirkin 1)

The Rosebush Murders (Hoopoe Publishing, 2012) is published upon demand as a trade paperback and available as an e-book (Kindle, e-Pub). It is sold by Amazon, Barnes & Noble, The Book Depository and other online sellers.

Hoopoe Publishing is Ruth Shidlo’s imprint.

Back cover copy:

In this first Helen Mirkin novel, Jerusalem-based Detective Inspector Helen Mirkin is challenged with solving the murder of psychologist Dr. Danielle Hall. Before much progress is made, a second murder occurs. Are they related?

The investigation leads DI Mirkin to a state-of-the-art art fertility clinic. How does this fit in? Is the killer trying to cover their tracks? Can they be stopped before more die?

VISIT Amazon for their “Inside-This-Book” feature, or order a free e-book sample excerpt. Better yet, order your own copy!

EXCERPT:

Rabbit at Top Speed

“When you have a sudden guest, or you’re in an awful hurry, may I say, here’s a way to make a rabbit stew in no time. Take apart the rabbit in the ordinary way you do. Put it in a pot or in a casserole, or a bowl with all its liver mashed. Take half a pound of breast of pork, finely cut [as fine as possible]; add little onions with some pepper and salt [say twenty-five or so]; a bottle and a half of rich claret. Boil it up, don’t waste a minute, on the very hottest fire. When boiled a quarter of an hour or more the sauce should now be half of what it was before. Then you carefully apply a flame, as they do in the best, most expensive cafés. After the flame is out, just add the sauce to half a pound of butter with flour, and mix them together…and serve.”

From Four Recipes, Leonard Bernstein

My Hoggie

Floating Prologue (Part I)

She closed the refrigerator door, and locked up — she didn’t want anyone tampering with her precious research. It was her baby and she knew without a doubt that it would take her far. The sky was the limit, but she would settle for Sweden.

She was not someone to be taken lightly. Not on your life.

The gall of it. Not even a real doctor. Well, she’d better not get too close…

Divide and conquer was her motto. If it had been good enough for Julius Caesar, it would suffice for her. Real power did not fall in one’s lap — one had to grab it with both hands. Sometimes she’d used her teeth or elbows, or even her feet. All in all, she’d come a long way.

No one would stop her now. And that meant no one. Not even Calvito, for whom she still had a soft spot, despite everything that had transpired between them. Things could only go so far.

It had been quite a struggle moving here from Peru and starting from scratch among the Jews of Israel. Back home she had been pampered. Her Pappie and his old cronies had seen to that. Nothing had been too good for his little princeling. He had been used to having had his commands carried out back in the old country. When circumstances had changed, despite having become a fugitive (especially as time passed and he was not caught), he had resorted to his old ways. So had the Colonel and the others. The older they became, the more entitled they acted, as if others were there merely to serve them. They bought whatever their hearts desired from locals only too happy to oblige, for the money was good and they were dirt poor.

When she was old enough to understand, she realized she could not accept what he had done, decided she would not be like him. She would atone for his sins.

In time, she became a well-known figure in the little rural community amidst the mountains. Whenever a goat was hurt, the peasants would present her with it, trusting her to nurture it back to health. La Alemana, they called her, amongst themselves.

She decided to become a doctor. Perhaps she could undo some of the harm her predecessors, especially her father, had done. Well, to undo was beyond her, but she would carry out the Hippocratic Oath to the full.

Day One

1

On a cool, crisp Jerusalem morning, the call of the tardy hen punctured the lazy quiet, inviting drowsy cats to stretch their legs before the tractor-like racket of determined leaf blowers drowned out the semblance of tranquility.

Grateful for the quiet, I listened to the early morning broadcast from the Voice of Music while wading through a pile of work I’d brought home. After a long while, I got up to fix myself a cup of Turkish coffee. I was standing impatiently next to the stove, waiting for the rich brew in the small finjan to boil, when the phone rang.

“Helen?” I recognized the unmistakable gravelly voice of my boss Captain Tamir, the police chief.

“Adam? Hang on a sec,” I said, stretching to reach the volume knob, killing the mezzo-soprano soaring above the chorus in Respighi’s glorious celebration of the birth of Christ.

“Listen, there’s been a shooting. Moriah asked us to handle it. A body was found in the Wohl Rose Park ten minutes ago — a jogger called it in. Officer Yarkoni is on his way to secure the scene. How soon can you get there?”

“I’m on my way.” I turned off the gas stove and took a swig of mineral water. The coffee would wait. Shedding my shorts and old T-shirt where I stood, I threw on my street clothes and ran a brush through my hair before locking up and zipping down the U-shaped stone staircase. Once ensconced in my emerald Compass Jeep, I shifted into gear and zoomed up the hill.

Leaving Shmaryahu Levin Street, I headed toward the hotel district and made a right just before the Renaissance, a sprawling, newly renovated stucco high-rise building, which seemed out of sync with the Jerusalem skyline; then sailed on until I reached the Rose Park.

Still early, this part of town was relatively free of traffic for Jerusalem Day, a day of festivities and the reason I’d planned to work from home.

2

07:30

From afar, the revolving lights of the blue-and-white sedan were visible but blurred and the late spring morning assumed a dreamlike, surrealistic quality.

Curious onlookers were gathered near the police car.

“Morning, DI Mirkin.” Having climbed the steps two at a time, I flashed my badge towards the solitary policeman on guard before realizing we’d once met. Another uniformed policeman joined me, directing me toward the cordoned-off scene in the arbor near the pond.

A trickling rivulet of blood still seeped through the limestone. A few feet further a crumpled body lay sprawled across the path. The dead woman’s arms were spread out against the earth, a bruised and swollen cheek grazed by a jutting rock in the shorn grass, her face disfigured like a Picasso painting. An eye peered unseeingly at me from a head lying cushioned in grass. Her white bandana had slipped from cropped hair; stained with fresh blood, it proclaimed surrender with both bang and whimper.

Despite having been a homicide detective for the past seven years and even longer on the force, I still felt that familiar, palpable tension when face-to-face with death at its most concrete. It did not get easier with time and whether I wanted to or not, I was forced anew to face the hour of my own death — if only fleetingly, the eternal Footman snickering.

Although no signs of struggle were evident, it was too early to tell with certainty. Turning toward Officer Yarkoni, whom the dispatcher had sent, I asked: “So Dan, an early morning jogger notified you of the shooting?”

“Yes, a Mr. Moshe Mizrahi called it in, practically hyperventilating. Had never seen a dead body before. He was sitting head down, hands over his ears, on one of those benches over there when I got here,” he gestured. “Here’s his name and work number.” Yarkoni handed me a piece of paper.

I gave it a quick glance before tucking it away in my pocket. “Thanks. It couldn’t have happened that long ago — the blood on the bandana is bright red,” I said, bending down to get a closer look.

“Yeah. See the point of entry here, just above the back of the neck?” He pointed in the general direction of the blood, which had stained the grass under her neck and continued along the limestone path.

“Right. The murderer stood behind her.” I looked around to see whether I could pinpoint exactly where. “Possibly over there, on those steps?” I added and went toward them, looking for shell casings and other telltale whispers of malfeasance. Twelve steps later, I realized a metal detector would be necessary, given the proliferating ivy. Fetching it from my kit, I was rewarded when it sounded — a .22mm empty cartridge that I promptly bagged.

“Looks like she was in the prime of life,” called Yarkoni, bending over the woman. “The waste of it.” He straightened up, looking slightly queasy.

Returning to the body, I bent down to get another close look. I didn’t comment on the untidy hole in her occipital lobe that the bullet had created, which appeared consistent with a small-caliber weapon. What was there to say?

Except that the bullet hadn’t come out through the other side.

Then I noticed some strange markings on her scalp, visible through her cropped hair.

Yarkoni had seen them too. “Weird. What are they?”

“Simulation markings, I think. To prepare a cancer patient for radiation therapy. The bullet never came out — see? — no exit wound. Except for the bruising, her face and neck are intact. It felled her.”

“Looks like this lady was doomed, huh?” exclaimed Yarkoni, shaking his head mournfully. “Both cancer and a trigger-happy-murderer on the loose…some people have no luck.”

“Yup…Crantz’ll get it out. Interesting to see what he’ll have to say.”

“Who’s Crantz?”

“Sorry, forgot you’re not with Major Crimes — the medical examiner.”

“I wouldn’t be able to do what you do, day in and day out.” He grimaced, before continuing, “What do you say – d’you think it could have been a terrorist?”

“Hard to tell yet. Events with a nationalistic background aren’t usually one-offs, are they?”

“How about suicide?”

“No. I don’t think she could have shot herself from the back.”

“Of course not.” He laughed, embarrassed at his ignorance in these matters. This was a far cry from what he usually did.

There was no handbag nearby. Going through the victim’s pockets felt somewhat intrusive but was necessary. We were a relatively small task force, which meant multitasking and familiarity with various aspects of detection and crime-scene analysis. Jerusalem was not Las Vegas.

I found a folded envelope, addressed to a Sheila Morenica-Hall of a local street, hidden in one of Jerusalem’s picturesque neighborhoods. I thought of how, against its will, Beit HaKerem was being invaded by the new freeway under construction. Ever since the rains had abated several weeks before, the pace of this unwelcome alteration had picked up.

When the photographer had taken her mandatory pictures and was packing her tripod, I allowed the corpse to be taken to the morgue by two attendants, newly arrived. As they lifted the dead woman, shrouded in black plastic and supine on the stretcher, her hand fell out, revealing an unusual and beautifully wrought wedding ring.

It seemed to open a window to the dead woman’s life, and I felt a twinge of sadness and regret for all that was irretrievably and wastefully lost, as I contemplated her hand, delicate yet strong; her fingers thin and elongated, such as a pianist might yearn for. Her fingernails were neatly trimmed and unvarnished, suggesting she had little use for frivolity and self-indulgence and liked herself as she was. The ring revealed, too, an appreciation of things classical, and even in death, lent her a feminine look. It felt like the ring of a loved woman. Her jeweled hand lent an aura of dignity to the degradation inherent in becoming a corpse, when the variegated themes, which were one’s life suddenly underwent diminution, like in a fugue, and the score, silenced forever, was packed into a plastic bag and dispatched to the morgue and the pathologist’s brain salad surgery.

“Might help identify her,” both Yarkoni and I uttered simultaneously, looking at each other, a joyless Greek chorus.

I told Yarkoni I would take it from there, but he elected to stay. While wishing my partner, Ohad, was with me, I nonetheless welcomed any help I could get. Yarkoni made a sweep of the adjacent area, beginning with some nearby dustbins.

Mounting the stone stairway, I walked to the observation point above the pond, making sure I wasn’t stepping on any footprints. Two birds chirped away on one of the acorn trees nearby. The fragrant perfume of roses spiced the air. Suddenly it felt good to be alive, momentarily cleansed from the pervading sights and smells of death, with which I was overly familiar. I looked around me. A few feet below, something floating on the muddy water next to a straggly water lily caught my eye.

Moments later, I was crouching beside the floating object and looking around for something with which to fish it out. Careful not to get my cross-trainers too wet, I used a discarded garden hosepipe.

It was a soggy appointment book and I noticed someone had stuck a stork sticker on the vinyl cover, currently nesting somewhat lopsidedly just above the letters CH, City Hospital’s insignia.

Eagerly, I attempted to pry open its pages, but they stuck together, stubbornly resisting my efforts. I stopped short of damaging them even further, and placed them on a large rock. Meanwhile, Yarkoni, having just returned from his short search, came up to take a look, noisily sucking some candy he said he’d found on the semi-circular bench near where the body was found.

“Apple-flavored,” he said, offering me some, but I declined. Who ate unsolicited candy left by an unknown person on a public bench? It wasn’t as though he were starving. I also wondered how he could possibly do so under the circumstances that brought us together. “Better save it for Forensics,” I suggested mildly. “It might be evidence.”

Spitting it out, he exclaimed, “Too sour, anyway.”

I smiled. He should have known better.

A dirty, gray crow cackled nearby on a patch of browning grass.

“Some of it might be legible once it dries out,” Yarkoni commented, referring to the appointment book, which might or might not be part of the physical evidence.

I silently wondered whether the book’s immersion in water represented a deliberate attempt to efface its words. Discolored ink, fading away under murky waters. How I wanted to visualize the scene before me, before the curtain had dropped.

As though he had read my mind, Yarkoni said, “Assuming it belonged to her, I wonder if the woman had something to hide? If so, from whom?”

“Who is the third who walks always beside you?

When I count, there are only you and I together,” I quoted.

“What?”

“But when I look ahead up the white road

There is always another walking beside you

Gliding wrapt in a brown mantle, hooded…”

“What the hell’s that?”

And then it struck me: might the woman first have met someone else, the appointment book an epitaph from a previous scene? The shooter, perched above the waterfall, observing, biding time? Her companion gone, the woman, thinking herself alone, remaining in the garden until the interceptor pounced, and the brute shot of a well-chosen bullet shattered the quietude and her life.

“He who was living is now dead…

Drip drop drip drop drop drop drop”

Questions, questions, everywhere.

“Helen? You with me?”

“Listen, I have some things to mull over. I really appreciate your help. See you.”

Yarkoni shrugged his shoulders and after a slight hesitation left, obviously feeling let down or even slighted.

Hoping he hadn’t taken offense where none was intended, I walked through the grasses near the pond, an area too ample to be cordoned off. My thoughts were interrupted when I noticed a young woman bending down to pick up something. I strode up to her, wondering whether it could be evidence related to the investigation.

She flashed me a big smile, revealing a missing front tooth. Seemed oblivious to what had happened, presumably had wandered here after my colleagues had packed up and left the scene. In her cupped hand, she held some berries, then raising her hand, pointed to the trees above, their boughs heavy with berries, some white, some pink, others purple-black.

Disappointed it wasn’t trace evidence, I nonetheless popped one into my mouth. “Delicious,” I said, picking yet another.

She smiled again.

“Have you been here long?”

She seemed surprised by my question. “Oh, no…I just got here. My son’s kindergarten is due soon, and I thought I’d come early, lend his teachers a hand.”

“Have you seen anything unusual since you got here?”

Like what?”

“Anything to set you wondering — maybe someone in a hurry, or hiding?”

“Sorry, Ma’am. No — I haven’t.”

“Right. Well, thanks anyway.” I moved on toward the kill spot, feeling the woman’s eyes on my back. I sensed she was puzzled by my questions.

Upon reaching the area, I contemplated the victim’s fate, her life derailed so brutally while in her prime. “I will find the killer,” I vowed silently, climbing a few steps. Standing roughly where I believed the murderer had stood, given the point of entry of the fatal bullet and the location of the empty casing, I tried to get a feel for what had gone down. Had the murderer attempted concealment among the rosebushes, or stood tall and erect on the bare steps? The former would have required greater marksmanship because of the arbor below.

I then noticed something I hadn’t seen earlier. Curious, on a fresh surge of adrenalin, I swooped down the remaining stairs, quickly reaching the semi-circle of benches, now shaded by the yellow rosebushes that covered the latticed wooden roof. It was behind them, on a little slope, well away from the stairs that overlooked the pond that a clump of white rosebushes stood. Between two, caught by a thorn, there was a snag of fabric.

Moving closer, looking out for possible footprints so as not to contaminate the scene, I disentangled the snippet from the recalcitrant thorn and examined it. It felt like a fine fabric, probably real silk. Was it the murderer’s? Bagging it, my mind raced ahead, while my foot crunched on something half-buried under the leaves. I bent over to pick it up. A green pillbox. Wondering whether it had belonged to the same person, a reasonable assumption given their proximity in an area not normally frequented, I retrieved it and zip-locked it. However much one sought them out, it was all too easy to miss vital clues out in the open, one of the many reasons why teamwork was important. Any chance you heard that Ohad?

An hour later and despite my ever-widening concentric sweep of the park, my search had failed to disclose either a purse or a briefcase. By now gloveless and just about ready to leave, I chanced upon a totally unexpected sight — that of a peacock attempting to eat a red apple someone had dropped. It kept getting stuck on its beak and then falling as he pecked at it again.

I grinned at the comical sight. An image of a peacock carrying a briefcase fluttered through my mind — wouldn’t that be lovely…Time to go deposit the still-wet appointment book, pillbox and fabric with the forensic lab.

The questions that had emerged clamored for resolution: Was this a random killing? Or in view of the victim’s cancer, a misguided, so-called mercy killing? Was the owner of the ring murdered because of who she was, what she knew, or what she was about to do? Had someone (a jilted lover, perhaps) decided to silence her once and for all? Had the appointment book marked the appointed hour for the woman to meet her would-be killer? Lastly I wondered just how the news would be met, and by whom.

I left the scene of the crime then called Adam Tamir, providing him with the bare bones about the case, before driving to the address on the envelope, which was near the park. Passing an ivy-covered government building, I made a left onto Yitzchak Rabin Boulevard and then Herzl, before entering Beit HaKerem, the quiet residential neighborhood where the Morenica-Hall family lived.

COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL (Ruth Shidlo & Hoopoe Publishing, 2012)

The Leonard Bernstein song “Rabbit at Top Speed” is reprinted by permission (full details within book).

A rose from my aunt’s garden

***

Did you like this Helen Mirkin novel?

Please take a moment to write a brief review, to help other readers decide whether they want to read this book. I will be thrilled.

Like the Author Facebook Page.

***

NON-FICTION

SCIENTIFIC EDITING:

Ronnie Solan’s “The Enigma of Childhood” (Karnac, 2015)

See trailer, as well as my review/interview on her website.